PHOENIX — It’s 110 degrees, there’s a pollution advisory in effect, and the cloudless sky provides no relief from the brutal sun. Even in the scorching heat, the platforms of the city’s light-rail system are packed with rush-hour commuters on this August afternoon.

“I find driving very unenjoyable. This saves money as well,” said Mike Stein, who uses Valley Metro Rail to commute to his job at one of central Phoenix’s many medical offices every weekday.

Even on days like this one, Stein prefers transit to driving. He’s one of the tens of thousands of Phoenix-area residents who have begun commuting by light rail since the system opened in 2008.

Most major U.S. cities view transit as key to serving their growing populations, reducing congestion and improving air quality by taking vehicles off the road. In the Washington region, where the Metro subway system is expanding into the outer suburbs and the light-rail Purple Line is under construction in suburban Maryland, officials are looking for ways to expand transit options for the same reasons.

But the future of rail transit in Phoenix is in jeopardy, as voters head to the polls Tuesday for a special election to decide whether to allow the city to spend any more money on rail development or instead invest more in auto infrastructure.

The issue is a crucial one. Phoenix, one of the hottest places in the country, also is one of the fastest-warming, and its fast-growing population, urban sprawl and scarcity of water have earned the desert metropolis a reputation as “America’s least sustainable city.”

Rail supporters say passage of the ballot measure could be economically and environmentally devastating.

“If Phoenix were to stop rail transit investments, it would be going back in time to an old auto-only mode that most cities in the U.S. — and the world — are moving away from,” said Marlon Boarnet, chair of the urban planning and spatial analysis department at the University of Southern California.

Phoenix is the country’s fifth-largest city, but it hasn’t been a major population center for long. The bulk of the region’s growth began after World War II, with the city’s population more than quadrupling between 1950 and 1960. Boarnet said urban development trends in that era strongly favored car travel.

“We were really building many cities, particularly outside of the Northeast, as — for lack of a better phrase — automobile-only,” Boarnet said. There was “very little transit, bus systems were an afterthought, nonmotorized mobility — walking, bicycling — the infrastructure often didn’t even exist.”

Phoenix, like other Western cities developing in the latter half of the 20th century, was designed for highways and sprawl. Transportation trends nationwide began to shift in the 1990s, Boarnet said. Many cities, including Los Angeles, Denver and Seattle, began to retrofit car-oriented infrastructure to include more transit options.

Phoenix followed suit, breaking ground on its original $1.4 billion, 20-mile light-rail system in 2005. Today, the 38-station system runs 28 miles, connecting the city’s downtown business core with the suburbs of Tempe and Mesa, stopping at Sky Harbor International Airport and Arizona State University along the way.

Weekday ridership is around 50,000, a number opponents point out is only about 1 percent of the metro-area population. The light-rail system, the 14th busiest in the country, has been expanded three times since it opened and was built using three voter-approved sales tax increases between 2000 and 2015, in addition to federal funds.

But as projected costs have increased, so has criticism. Since 2015, the budget for planned expansions has more than doubled to $1.35 billion. Construction costs have increased, plans have grown to include a new downtown transit hub, and a federally required contingency budget was added. Opponents say taxpayer money is being wasted, while rail advocates say federal grants will make up much of the difference and the contingency money may never be spent.

Such scrutiny was enough to convince the Phoenix City Council in March to shelve an expansion planned for the western part of the city and reallocate more than $150 million to street repairs.

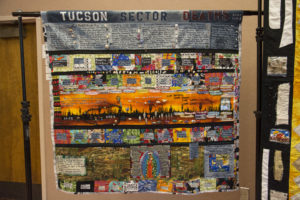

The next planned phase of development, set to break ground this year, would extend the system five miles into the southern part of the city. But that, too, has sparked criticism, with a group of South Phoenix residents and business owners leading the opposition. In addition to the potential impact on businesses, the proposal has raised concerns about gentrification in South Phoenix, a lower-income part of the city with a large Latino and African American population.

“All these small businesses have been here for decades and you’ll get wiped out and be displaced,” said Susan Gudino, of Building a Better Phoenix, the group leading the fight to end rail funding.

Gudino said the city’s promises for assistance don’t convince her that small businesses in her community would survive the planned four-year construction period for the next phase. She also worries about the changes to traffic flow that would be caused by converting roadway to tracks.

“All the small businesses depend on the car traffic going by,” she said.

The complaints and concerns are similar to those heard during early discussions about Maryland’s Purple Line, now under construction. The 16-mile project is being built through a $5.6-billion public-private partnership,one of the largest of its kind underway in the country.

Skepticism over the South Phoenix extension swelled into the Proposition 105 ballot measure, which would halt not only the South Phoenix line, but any future rail development in the city. If passed, the city would turn away billions in federal transit grants and redirect previously approved sales tax funding to road improvements. In a car-centric city where many roads are in disrepair, those funds could have a more immediate effect, rail opponents say.

Such organized opposition has killed transit projects elsewhere. Donors to Building a Better Phoenix include the Arizona Free Enterprise Club, a group with ties to Americans for Prosperity, an influential political advocacy organization funded by oil industry billionaires Charles and David Koch. David Koch died Friday. Americans for Prosperity has campaigned against transit in Arkansas and Utah, and in 2018 the group led a successful door-knocking campaign to defeat a light-rail project on the ballot in Nashville.

“We’ve tried to watch and learn from Nashville,” said Phoenix Mayor Kate Gallego (D), who opposes the ballot measure. “I’ve tried to do town halls and community meetings in every corner of the city so people can understand why [light rail] matters.”

Gallego attributes the revitalization of the city’s downtown to the light-rail system and notes that Phoenix is the largest city in the country not connected by Amtrak. To compete economically, Phoenix needs more rail development, she said.

“It’s also a value statement. Do we want to make sure that people in our community have access to good schools, good jobs, medical care? Do we want to make sure that people have chances at affordable housing where a lower percentage of their budget can go to transportation so they don’t need a car? Great urban cities have options,” Gallego said.

Easing traffic is an immediate goal, but the mayor also is concerned about the city’s pollution and climate in the long-term. The American Lung Association ranks Phoenix among the worst places for ozone pollution in the United States, and Climate Central projects Phoenix will have 147 days a year with a heat index above 105 degrees by 2050. Those public health concerns could bring major economic losses for the city.

Rail transit could help, Boarnet said. He co-wrote a 2012 study of households near a newly opened Los Angeles light-rail line and found, on average, access to the train led families to reduce driving by 10 miles per day, or about 40 percent. Multiply those numbers by the thousands of people living near the rail lines and the effect on traffic, smog and carbon emissions is measurable, Boarnet said.

“In a place like Phoenix, these same factors would work. We don’t have any reason not to believe that,” he said.

Boarnet cautioned that light rail alone will not solve climate and pollution problems. A city needs multiple transit options, as well as land-use policies that encourage denser housing near transit to be fully effective, he said. Although the nationwide trend is toward more public transit, in many cities, ridership is declining.

“I do not interpret this as ‘people don’t like the bus and never will,’ ” Boarnet said. He views the trend as an indication that cities still have work to do to provide the most effective transit systems.

The challenge is getting big-picture goals to resonate with voters. Boarnet said transit-related votes can be difficult because they ask voters to imagine results that might be decades away.

“This is literally a play for what should Phoenix look like about 20 to 30 years from now,” he said.

It’s a future he can see clearly though. Rail transit has the capacity to move tens of thousands of people per hour, while freeways might move only a small fraction of that. The Phoenix area is growing by more than 200 people per day. Sooner or later, the city will simply run out of space to efficiently move everyone by car, Boarnet said.

“Phoenix voters may not feel like they’re there yet,” he said. “The difficulty is, if they don’t do anything else, they’re going to get there eventually.”

Read this story on Washington Post