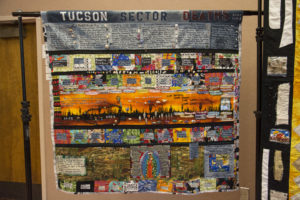

The 14 quilts that make up the Migrant Quilt Project are each unique. One looks like a large American flag, one shows silhouetted cacti against an orange sunset, one is quilted with rows of small white skulls. But all of the quilts share one feature: long lists of names, such as Jose Lara Avila, Margarita Rios Rodriguez, or Rufino Hernandez. But the most common name, listed again and again on every quilt, is desconocido, unknown.

The Migrant Quilt Project is a folk art memorial to the hundreds of people who die each year attempting to cross over the border from Mexico into the United States. Alongside the lists of names, small scraps of jeans, handkerchiefs, and other personal items found in the desert are sewn into each quilt to symbolize the human side of illegal immigration. Though illegal immigration to the United States has slowed in recent years, routes taken by migrants have become increasingly dangerous. The organizers of the quilt project hope to bring attention to the continuing issue of migrant fatalities.

“When [the quilts] are hung en masse, they are stunning and it’s overwhelming,” says Jody Ipsen, the project’s director, as she prepares for a showing of the quilts at a church in Oro Valley, Arizona. “More than anything, people say, ‘I had no idea. I had no idea people were dying in the desert.’”

Ipsen has lived in Tucson, Arizona, about 60 miles north of the border, since the 1960s. She says for years she’s watched the border become more militarized. But it was on a camping trip in 2005 that she really started to think about how dangerous and politically charged it had become.

Ipsen was hiking in the Arizona desert when she came upon a trail covered by discarded clothing, diapers, water bottles, and tuna cans. “At first I was appalled,” she says. She thought that the items were just litter, carelessly abandoned in an otherwise pristine natural area. But when she realized she was looking at the remains of a migrant camp, her concerns changed.

She began volunteering with humanitarian groups that provide water and aid to people crossing the desert. She learned more about the challenges faced by undocumented migrants, often fleeing violence in Central America. She also volunteered with desert cleanup organizations, with whom she’d sometimes dispose of clothing or trash left by migrants.

“I felt really compelled, like, maybe there’s something we can do with this migrant clothing we find in the desert to speak to the issues in a more in-depth way,” Ipsen says.

Ipsen knew of the NAMES Project and its AIDS Memorial Quilt, with its thousands of six-foot-long quilted panels made by volunteers to remember loved ones lost to the AIDS epidemic. She wondered if she might be able to launch a similar memorial for undocumented migrants who had died on their journeys to Arizona. But Ipsen had spent her career in the publishing industry and had never made a quilt. So she partnered with nonprofits, church groups, and individual volunteers from around the United States and started what would become a years-long, collaborative sewing effort.

Each quilt represents one year of fatalities that occurred within the U.S. Customs and Border Protection Agency’s Tucson Sector, which covers most of Arizona’s border. For some years, the quilts list around 100 people, both named and unknown. Other years, they list nearly 300. The quilts incorporate personal items found in the desert, believed to have belonged to migrants.

Though the quilts are meant to memorialize those who have died in the deserts, the scraps of clothing used do not come from sites where bodies were found. Rather, they are items that have been abandoned under the desert sun, usually found in trash heaps along with food scraps and other garbage. On the rare occasion Ipsen and her volunteers find a backpack or piece of clothing with some form of identification on it, they will hand the item over to the Consulate of Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala, or appropriate country.

Peggy Hazard is a retired gallery curator who now helps Ipsen coordinate the Migrant Quilt Project. She also helped make one of the quilts.

“The whole experience was emotionally fraught,” Hazard says.

She has been a quilter most of her life, but says working with pieces of worn-out jeans and sun-faded bandanas felt different. The quilt she worked on also included a set of hand-embroidered cloth napkins.

She will never know to whom those belonged, but she says, “Those particularly moved my heart because I knew somebody had spent the time to stitch those and then send them with their loved one.”

What troubles Ipsen and Hazard is that migrant fatalities have not declined over the past decade. The clandestine nature of illegal immigration makes data difficult to accurately collect, but the numbers that are available suggest the percentage of migrants who die crossing the border is growing.

The Missing Migrants Project of the UN’s International Organization for Migration reports more than 250 migrant deaths along the U.S.-Mexico border so far for 2017, slightly more than the same period in 2016. Meanwhile, U.S. Customs and Border Protection reports a nearly 40 percent decline in apprehensions of migrants this year, a signal that fewer people seem to be making the journey than in prior years.

“Even though fewer migrants are crossing, they’re taking more risks,” Julia Black, project coordinator with the Missing Migrants Project, says in a phone interview from her Berlin office. “The data indicates that it is more dangerous for migrants crossing into the U.S. this year than last year.”

Since 2012, the Migrant Quilt Project quilts have been displayed at border issues conferences, museums, churches, and universities around the country. Ipsen says she hopes showing the quilts will honor those who have lost their lives, and also inspire policy change to bring an end to border fatalities.

Those kinds of efforts to raise awareness are crucial, according to Reyna Araibi, a spokesperson for Colibrí Center for Human Rights.

“What’s really going to change policy is these really human-centered narratives,” Araibi says. Her organization provides resources for families searching for migrants who have gone missing crossing the border, and currently has more than 2,400 open cases. “You cannot make any type of progress on this issue if we’re not talking about both the numbers and the humans behind it.”

The idea of using quilts to spark political conversation is nothing new, Hazard says. Abolitionists, suffragettes, and leaders of the temperance movement are known to have used quilts as a form of activism. “For a long time women didn’t have many rights, so women used the power of the needle, whether embroidery or making quilts, to get their point across,” Hazard says.

Ipsen says she hopes the quilts illustrate a problem that anyone can relate to, even while border policies and immigration issues have become more politically divisive.

“Whatever your feelings are, whether they’re illegal or not, these are human lives, people with families,” Ipsen says. “Human life is sacred.” She says she and her volunteers will keep making quilts “until there are no more deaths in the desert.”

Read this story on Atlas Obscura